Nebraska sues Colorado over South Platte River water

Water20-RFP-072825

If ever proof was needed for the Western adage that “whiskey is for drinkin’, water is for fightin’,” one has only to look at the recent lawsuit filed by Nebraska with the U.S. Supreme Court.

The lawsuit alleges Colorado is deliberately delivering less water than is called for in the 1923 South Platte River Compact. That compact requires Colorado to deliver 120 cubic feet per second (cfs) of water across the state line during irrigation season, which runs from April 1 to Oct. 15 each year.

The compact, which has an adjudicated water decree of June 14, 1897, is junior to many other water rights along the river in Colorado, and the 120cfs is required only after senior decrees have been satisfied. In an increasingly hot and dry climate, that means less water coming down the South Platte, from which Colorado irrigators are still pulling their rightful share. Municipalities and even some industries also have water rights senior to the compact.

Nebraska’s lawsuit claims Colorado is allowing irrigators with water rights junior to the compact to divert water even when less than 120cfs is crossing the state line, a charge Colorado officials vehemently deny.

Joe Frank, manager of the Lower South Platte Water Conservancy District, told The Fence Post it should be no surprise to Nebraska that there just aren’t 120cfs in the river at the state line sometimes.

“Bottom line is that there has never been a guaranteed delivery requirements of 120cfs under the South Platte Compact,” Frank said. “Historically, there’s often not even 120cfs available at the state line, simply due to the fact that there is a very limited native supply of water, especially in drier years, and there are high irrigation demands and diversions from upstream irrigators that are senior to (the) June 1897 compact date.”

THE CANAL

The lawsuit also contends that Colorado is unnecessarily obstructing Nebraska’s effort to build what is called the Perkins County Canal.

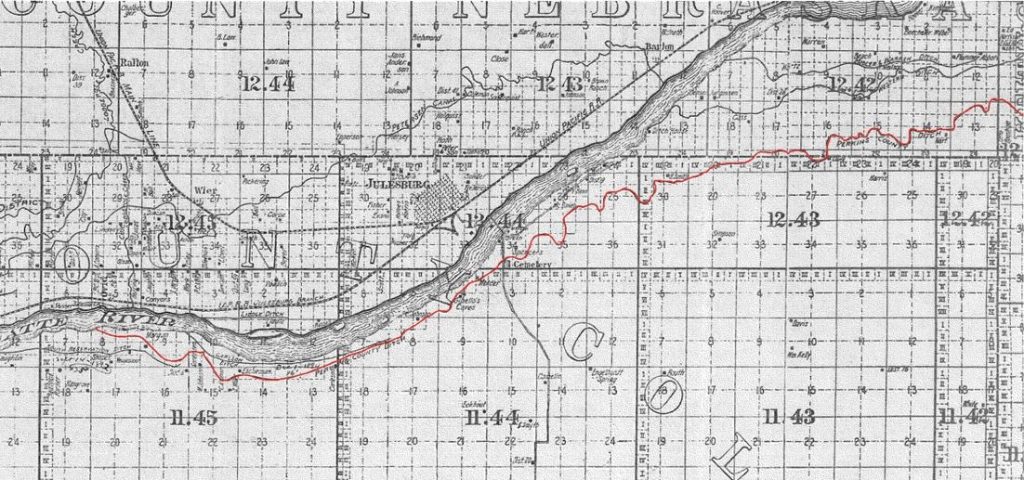

Nebraska had started to build the canal in 1891, with the intent of diverting water from the South Platte near Ovid, Colo., and delivering it to a reservoir in Perkins County, Nebraska, for irrigation. That project was abandoned as too costly and unlikely to deliver any beneficial amount of water. Remnants of the canal still exist, most prominently along Interstate 76 near Julesburg.

When the South Platte Compact was negotiated more than 30 years later, Nebraska was granted the right to receive 500cfs during non-irrigation months (mid-October to April 1) on the condition that it take the water via the Perkins County Canal. The compact also grants Nebraska the right of eminent domain to condemn Colorado property on which to build the canal.

It has been speculated that the conditions for accessing that 500cfs during the winter were intended to make the canal unfeasible. By 1923, extensive irrigation along the South Platte had transformed the river from a seasonally dry creek bed to a year-round flow, but the supply was still unreliable. Over time, the river flow became more dependable and water seeping back into the river from irrigated lands literally built up the river. The addition of 215,000 acre feet of water — roughly 71 billion gallons — each year from the Colorado-Big Thompson project starting in 1956 was the equivalent of a second Cache la Poudre River in the South Platte Basin.

None of that changes the fact that there is a finite amount of water available to Coloradans each year and, being a headwaters state, Colorado is responsible for sharing its water with downstream states. The state is party to nine interstate river compacts and abides by two Supreme Court equitable decrees, two international treaties and two memoranda of understanding.

URBAN DEVELOPMENT

Colorado also continuously experiences some of the highest population growth in the country, almost all of it in the South Platte Basin. In an attempt to prevent urban water needs from outstripping supplies and causing the drying up of farmland, the Colorado Water Conservation Board commissioned a statewide water plan and, in November 2015, that plan was presented to then-Gov. John Hickenlooper. While the plan covers all nine of Colorado’s major drainage basins, particular attention is paid to the Colorado and South Platte basins.

Those attending the presentation in History Colorado’s conference room weren’t the only ones interested; Nebraska was listening, too. They were as startled as anyone that, according to the Colorado Water Plan, by 2030, the state would be in a serious water deficit as urban development along the Front Range corridor continued unabated.

As a result of the 2015 plan, Colorado water interests got serious about identifying feasible water storage projects. Although nearly every drop of water that normally flows down the river is already claimed, there are times during spring snowmelt and occasional floods when millions of acre feet of water rush past with no way to store it for beneficial use. To spur the development of storage plans, the CWCB funded a series of studies and in December 2017 the South Platte Storage Study was unveiled. The study included more than 230 possible water storage ideas, few of which are feasible or affordable. Meanwhile, the Lower South Platte Water Conservancy District, headquartered in Sterling, announced it was working with the Parker Water and Sanitation District to store and divvy up 76,000 acre feet of water that escapes Colorado each year during peak runoff and occasional flooding. Part of the water would be pumped up to Parker and the rest would be apportioned among irrigators along the lower reaches of the river.

In 2019 Nebraska’s water experts decided to interpret Colorado’s water storage plans as detrimental to the Cornhusker state and announced they were going to resurrect the moribund Perkins County Canal project. Reaction in Colorado was swift; pulling 500cfs from the South Platte at Ovid would cause catastrophic damage to the river, and not just in Colorado. Among the immediate concerns: Water augmentation projects, meant to replace water pumped during irrigation season, would be wrecked. The Platte River Recovery Project, protecting whooping crane habitat deep in Nebraska, would be ruined. The landscape had changed dramatically since 1891, not the least of which is a major interstate highway slicing through the canal’s route.

Whether the canal is even feasible, let alone whether it will be built, depends on whose engineers one talks to. At the end of 2022 Zanjero AMS, a Sacramento, Calif., water consulting firm, issued a report predicting the project could capture and store up to 78,000 acre feet of water for use in Nebraska. Water engineers in Colorado have called the Zanjero report a “overly optimistic.”

Colorado state leadership decided to treat the project as a negotiating strategy and politicians have tried to get Nebraska to sit down and talk about sharing the South Platte beyond the margins of the 1923 compact. Jerry Sonnenberg, a state senator from Sterling at the time, said he reached out to Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts numerous times, to no avail. Colorado Gov. Jared Polis visited northeast Colorado in July 2022 to see for himself the areas in Colorado where the canal would be built. He said at the time he didn’t see how the canal could ever be built.

“We think Nebraskans will come to their senses, and realize it’s a big boondoggle,” Polis said. “It’s very unlikely that the project will come to fruition. If their approach is adversarial, then we will deal with that, but there are many, many difficulties in the way of (the project.)”

Most of the preliminary legal skirmishing has taken place in Sedgwick County, where the canal would drain water from the South Platte. Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser has assured the landowners there his office will do all it possibly can to protect their property rights. When landowners refused to consider offers from Nebraska to buy land for the canal, Nebraska sent letters to the effect that they are subject to having their property condemned through use of eminent domain. Denver attorney Donald Ostrander wrote to Nebraska State Engineer Matthew Manning that attempts at condemnation could end up costing Nebraska millions in legal costs; Manning replied with a terse “we’re not afraid of you” message.

Legal fights over water rights usually take years to play out and cost millions of dollars; this lawsuit will be no different. In a statement issued on the heels of the filing, Colorado AG Weiser said Nebraska’s actions will only spur further water storage development in Colorado.

“Nebraska has now set in motion what is likely to be decades of litigation,” Weiser said. “And if, after decades of litigation, the court allows Nebraska to move forward with its wasteful project, Nebraska’s actions will force Colorado water users to build additional new projects to lessen the impact of the proposed Perkins County Canal.”