Klinglesmith family provides update on wolf depredation in Colorado

Update on the apparent wolf depredation and cattle losses found in Meeker, Colo., on Oct. 4, 2022.

As reported in the article dated Oct. 7, 2022, we found 18 calves dead within 1.5 miles of each other. The investigation performed with Colorado Parks and Wildlife and Wildlife Services pointed to wolf depredation.

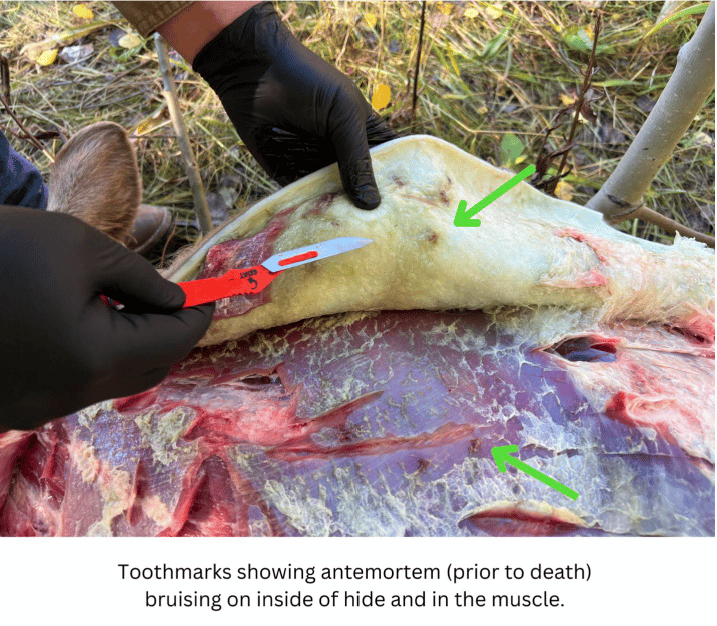

Several carcasses had tails missing and marks consistent with canine teeth. The carcasses had hemorrhaging in locations where investigators are trained to look when distinguishing canine depredation from that of bear and lion (see APPENDIX A photos).

After a long day of necropsies, we spent time together trying to consider any other possible cause of death. With several decades of experience managing livestock in the area and several decades of wildlife management by the DWM and Wildlife Services, we could not come up with another answer that was supported by the evidence.

We then made the decision that our neighboring producers would need to be notified immediately. We realized by doing so, this story would be in the wind and come out in the press after traveling through social media. We felt it was important to speak directly to the press so the most accurate information would be reported.

In the days following, we continued our annual gather back to ranch headquarters for fall shipping. Along the way, we started finding a dead calf every few miles. At this point we brought in veterinary help with the investigation to look at any other possibilities. These investigations brought clostridium chauvoei (black leg) to our attention.

As we researched this clostridial disease and outbreaks in other regions of the world with large casualties, some similarities to this situation were recognized. The following are quotes from case studies involving outbreaks of this disease.

“The spores are harmless to the animal until wounds, trauma, or bruising damage the muscle tissue in such a way that an environment is created that is favorable for the the spores to begin their vegetative growth.” (Hart, SDV Cumberland)

“The spores remain dormant until a poorly understood triggering event occurs, which may include local tissue hypoxia due to traumatic injury.” (DeLay et al.)

“The organisms can survive for months to years without deleterious effects to the host. However when the oxygen tension drops in areas of muscle in which spores are present, usually as a consequence of blunt trauma and associated tissue hemorrhage, degeneration, and necrosis, the spores germinate, proliferate, and produce toxins that are responsible for most clinical signs and lesions of black leg.” (Abreu et al.)

Therefore, the most likely scenario would be the following:

An apparent canine attack may have triggered the onset of a still-inconclusive cause of death. We made a management decision to change from giving a spring and a fall dose of 8-way vaccine, to giving two fall doses prior to weaning. The 8-way vaccine contains and protects against eight clostridial strains. This change in vaccine protocol allowed us to focus spring immune responses on the four main respiratory viruses, and Pasteurella. Our goal in changing vaccine protocol was to administer fewer antibiotics throughout the summer months for respiratory sicknesses; and we were successful in this aspect.

USING RESEARCH AND EXPERIENCE

The good news is that, if in fact a clostridial was triggered by an attack, with a return to our original vaccine protocol we should be able to avoid the heavy casualties. We should be able to limit our losses to a few depredation casualties, a possible reduction in weaning weights and breeding stock conception rates due to stress. This fits the research and experience consistently reported in the Northern Rockies.

However, pathology results from samples sent to veterinary diagnostic labs did not show evidence confirming clostridium chauvoei as the cause of death.

“There is significant autolysis in the skeletal muscle sections which makes interpretation difficult. However, there is no evidence of necrosis or active inflammation to suggest black leg.” (Colorado State University Diagnostic Laboratory, Oct. 20, 2022)

“There are no microscopic lesions in the tissues examined that explain the cause of death in this animal. There is no evidence of inflammation, necrosis or degeneration.” (Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory, Oct. 21, 2022) (See APPENDIX B)

In closing, we are working closely with CPW, Wildlife Services, and veterinarians to verify cause of death, and whether wolves are in the area. Prior to October 2022 there were eight officially reported wolf sightings in the area over the last few years. Since the publicity, there have been many more reported wolf sightings, but none have yet been verified. There has also been a report of a pack of dogs. This lead is being heavily investigated as well, but also, has not been verified.

This whole process has taught us that these investigations will require a lot of time and effort on the part of CPW staff and landowners in rural Colorado. We promise to continue to work with the local staff here in Rio Blanco County to figure out whether wolves are present or if there is another explanation for the apparent stress and trauma these calves suffered.

As a multi-generational ranching family, we are committed to running a progressive livestock and wildlife operation. However, we are also committed to working with those in our state and keeping them updated on our scenario.

Bridging the gap that exists between urban and rural is important to us. The future of livestock production in our state remains equally important. We understand this is a highly contentious issue, but hopefully we can agree on the fact that collaboration is key to working toward a solution. The relationship between state agencies, livestock associations, the Colorado public, and ranching families is crucial in moving forward with the process of coexisting with all wildlife on our landscape.

APPENDIX A

Opinion-RFP-120522

APPENDIX B

Sources:

Abreu, Camila C., et al. “Pathology of Blackleg in Cattle in California, 1991–2015.” Journal of

Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, vol. 30, no. 6, 2018, pp. 894–901.,

https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638718808567.

Colorado State University Diagnostic Laboratory, Oct. 20, 2022

DeLay, Josepha, et al. “An Outbreak of Blackleg (Clostridial Myositis) in Unvaccinated Beef

Calves.” An Outbreak of Blackleg (Clostridial Myositis) in Unvaccinated Beef Calves |

Animal Health Laboratory, https://www.uoguelph.ca/ahl/content/outbreak-blacklegclostridial-

myositis-unvaccinated-beef-calves.

Hart, SDV Cumberland, Keith. “Case Notes.” Blackleg in Cattle, Mar. 2011,

http://www.flockandherd.net.au/cattle/reader/blackleg.html.

Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory, Oct. 21, 2022